Japanese portraits are contemplative, commemorative. No! They were interested in light and shade in these sculptures. The Western generalization about Japanese art was abstract, not interested in the reality, light and shade, didn’t bother. But when we look at the particular group of art done in the medieval period in the area of portraiture, there’s an extraordinary degree of realism explored by the artists. Yoshiaki Shimuzi: The representation of reality is not sometimes the main concern in Japanese art. The bee man was real, the bees were real, the man was real, the photograph was real. The bees didn’t just happen to all of a sudden-uh oh, he’s walked into a swarm of bees, quick let’s get the white paper. He met this bee keeper, this bald guy, and so he said, “Well, let’s make him the bee man.” And so he painted him with honey. Stephen Perkinson: The idea that a portrait can ever be truly truthful, fully truthful, is itself a sort of a myth.ĭavid Ross: Avedon used the seamless white backdrop because it allowed him to remove all traces of photographic artifice. She said, “Well, it doesn’t look like me.” And he said, “Oh, it will.” So it’s as if he invented the portrait to invent the way that she would become. Gertrude Stein was very distressed with how she looked. Susan Sidlauskas: He was looking at sculpture that would simplify, to an almost abstract extreme, the features of the face, and create a kind of mask behind which the person existed. He paints her face and then he paints it out, and he paints it again and then he gets rid of it.Īnn Temkin: And the story goes that he actually abandoned it and left Paris to spend the summer in Spain, where he was very affected by ancient Iberian and African art. They sit opposite each other and he keeps painting out her face. Picasso’s a young struggling painter of enormous ambition and arrogance.

Susan Sidlauskas: When Picasso meets Gertrude Stein, she’s already a literary figure of great note. So his body fills the entire canvas to convey his power or authority.Īnn Temkin: We read a portrait not just in terms of who’s painted, but who’s painting, and how they sort out the kind of strange situation that that particular encounter really is. So, who has the power there? Well, Henry VIII was famous for lopping off the heads of many of the wives that he didn’t like, so you can imagine that Hans Holbein would be very anxious, that he would please Henry VIII.

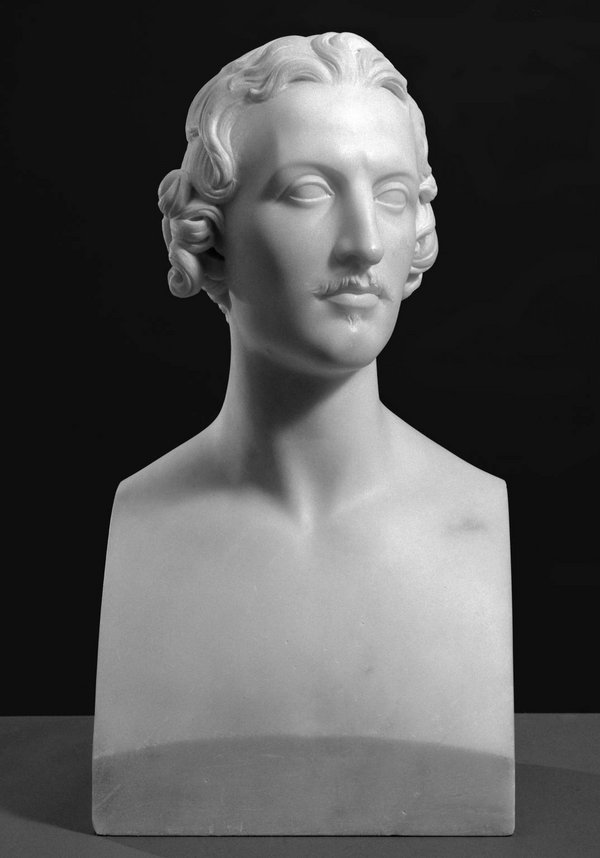

You might have a powerful figure, you might have King Henry VIII, commissioning a painting, a portrait by Hans Holbein. Susan Sidlauskas: There is a contest between them, and you could say that it’s up for grabs throughout history as to who wins. The sitter is trying to convey a sense of who they are to an audience that they want to impress. Stephen Perkinson: The artist is trying to demonstrate his or her skill at capturing a likeness. Susan Sidlauskas: The notion of portraiture is such a slippery one, because in many ways both the subject and the portrayer want to control the event. Susan Sidlauskas: Given the fact that faces are so critical to us, it’s natural that portraiture as a genre would have been one of the ascendant art forms for thousands of years. You have this need to recognize, to make distinctions, to read emotions it’s absolutely crucial. Kehinde Wiley: Because we’re selfish, we want to see elements of ourselves in everything.Īnne McClanan: You can see how it’s almost fundamental for survival. An animal looks at your face.ĭavid Lubin: Before we learn to talk or walk, we learn reading the signals in a person’s face. Across the themes and styles in this exhibition, it is evident that portraiture allows for a breadth of expressiveness, a scrutiny of the self, and the occasion to connect with those around us.Ĭurated by Storm Tharp in collaboration with Grace Kook-Anderson, The Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Curator of Northwest Art.Susan Sidlauskas: The face is the first thing we’re drawn to. How artists in this collection have chosen to do this is remarkably varied, offering an alluring examination in itself. For an artist, capturing a literal likeness is far less important than grasping the essence of a person or the moment in time. As he combed through the collection, some themes in portraiture rose to the surface: the self-portrait, artists and friends, family, psychological space, and making present those who have been less recognized. For this exhibition, the artist Storm Tharp was invited to help select works from the collection through his keen eyes as a fellow portraitist. In the rich tradition of portraiture reflected in Northwest art, there is an exemplary range of individuals and styles of depiction. Portraiture from the Collection of Northwest Art

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)